Quercus · 432 pp · 2010

Edith Cavell was shot at dawn by the German occupying army in Brussels on 12 October 1915. Her crime had been to smuggle allied soldiers, separated from their regiments, out of war-torn Belgium. In her fifty years of life she moved from the tranquillity of her childhood as a vicar’s daughter in rural Norfolk, to the constraints of being a governess to other women’s children, to fulfillment as a reforming hospital matron.

She was a pioneer nurse at a time when it was emerging as a trained profession, and not, as Florence Nightingale put it, ‘just a job of last resort for those too old, too weak, or too drunk to do anything else’. She trained at the Royal London, a flagship Victorian training hospital. In 1907 she was invited by a leading Belgian surgeon to go to Brussels as head matron of his hospital and set up a training school for nurses there. She introduced modern nursing practice into Belgium.

On the face of it she was the archetypal Victorian matron. ‘The dusting should be done by ten nurse’ she would say as she wiped her finger along the iron bedsteads. But behind her starchiness the motivation of her life was sublimely romantic. ‘The noble profession of nursing’ she told her probationers, would lead to ‘the widest social reform, the purest philanthropy, the finest humanity.’

The First World War interrupted her work. In August 1914 she watched as 50 thousand German soldiers marched into Brussels. After the battle at Mons, where the German army won, wounded allied soldiers, separated from their regiments, hid in woodland and ditches. If picked up by the Germans they were shot or sent to prisoner-of-war camps in Germany. A resistance network grew up to help them. In Brussels, Edith Cavell’s nursing school became a central safe house for them.

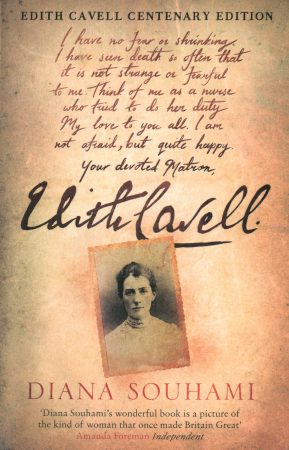

Her network was watched and rounded up. Of those arrested Edith Cavell was singled out for execution because she was English. She spent ten weeks in solitary confinement. The night before she died the English priest from the church where she had worshipped gave her communion. ‘I have no fear or shrinking’ she told him. ‘I have seen death so often that it is not strange or fearful to me.’ He told her she would be remembered as a heroine and a martyr. ‘Don’t think of me like that,’ she said. ‘Think of me as a nurse who tried to do her duty.’ And she made the comment now engraved on her monument in Trafalgar Square: ‘I realise that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.’

What prompted me to write about Edith Cavell was the idea of altruism, the concept of goodness. In two years of working on this book I have kept unswerving respect for her. ‘I told you devotion would bring its own reward’ she told her nurses. She was a true public servant. Her work was prompted by love. It is hard not to be moved by her story. Her character lit up the dark times through which she lived and our own times too. She became a subversive because of her unflinching moral view.

D.S.

UK: Hive · Foyles · Waterstones · amazon · Kindle

US: IndieBound · BAM · Powells · amazon · Kindle

Read an excerpt

Birth

Edith Cavell was born in the village of Swardeston on a rainy Monday three weeks before Christmas in 1865. The village – sward and town – was four miles from the city of Norwich and had a population of 350. Most of its 900 acres were owned by the lords of Swardeston Manor and Gowthorpe Hall, the Gurneys and the Stewards, who traced their fortunes, their favours from the Crown, back to the sixteenth century. Villagers owned very little – a cottage perhaps and a garden. There were six farmers, three gardeners, two blacksmiths, a cooper, a mole catcher, a butcher, a wheelwright, a carpenter, a bricklayer, a schoolmistress, and the keeper of The Dog Inn. Their surnames were Skinner, Miller, Till and Piggin, they handed down their trades and skills father to son, married into each other’s families and on marriage certificates often ‘left their mark’ in lieu of signature, for not many had been taught to write. They looked out for each other, knew the vagaries of the weather, how to stack the hay, shoe the horses, make cider.

It was a way of life that seemed immutable, quintessentially English, governed by the seasons, the long nights of winter, the festivals of harvest and Christmas. War was a distant belligerence: the conflicts of empires – French, Russian, Prussian and British ambitions for hegemony – were irrelevant and remote. The preoccupations of Swardeston were with planting and ploughing and the rhythms of village life.

For Edith’s father, the Reverend Frederick Cavell – a stern bewhiskered man – Christmas was his busiest time. He had been the village’s curate for less than two years. As well as all his pastoral duties he was supervising – and financing – the building of a new vicarage which was to be his family home. He had married the previous year, at the age of forty, and this was only his second Christmas as a family man.

His young bride, Louisa Cavell, was twenty-six. She gave birth in the front bedroom of the eighteenth-century farmhouse her husband was renting until the vicarage was finished. The room was quiet and comfortable, aired and clean with a view over fields of pasture. A fire burned in the grate and all was prepared according to the latest edition of Dr Churchill’s Manual for Midwives, first published in 1856 and now in its fourteenth edition.

The midwife was a local woman whose only qualification was experience and a willingness to help. It was to be thirty-seven years before a Midwives Act dictated standards of proficiency. Even so, it was safer to give birth at home and in the country than in hospital or the city. With home births, whatever the shortcomings of the local helper, five women in every thousand died in childbirth. In hospital it was thirty-four. Florence Nightingale, whose revolutionary nursing methods were to inspire this particular newborn child, in her Notes on Nursing advised mothers to avoid hospital ‘even at the risk of the infant being born in a cab or a lift’. Childbirth, she said, which was not a disease, in hospitals had an equivalent fatality rate to the major diseases. The cause was cross-infection from other patients and was part of hospital life. Quite why this contagion happened was not known. She blamed ‘foul air and putrid miasmas’, expectant mothers crowded in together for weeks at at time, students going from a surgical case in an operating theatre to the bedside of a ‘lying-in’ woman.

She made a plea for cleanliness and improved nursing standards and recommended that childbirth units be separate from hospital wards. She wanted no more than four beds to a unit, each bed with its own window and privacy curtain. She wanted polished oak floors, sinks with unlimited hot and cold water, clean linen, renewable mattresses.

Her plea coincided with breakthrough research in antiseptics, research that crossed national boundaries. In 1864 the French Academy of Sciences accepted the hypothesis of Louis Pasteur, a chemist from the Breton town of Dole, that sepsis happened not spontaneously, as was supposed, but through the spread of destructive micro-organisms invisible to the naked eye. There was ‘something in the air’ that was harmful and needed to be destroyed and kept away from a wound.

Joseph Lister, a British surgeon was receptive to Pasteur’s experiments and in his own operations set out to block the path of these organisms by using carbolic acid as a barrier. It proved revolutionary. It allowed him to sew up an operation wound without it turning septic. By 1867 he was writing in the Lancet on ‘the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery’ and was struggling to convince the medical profession that his and Pasteur’s findings meant they must change their way of working: that they must not go from conducting an autopsy, to a woman in labour, without changing their clothes and washing their hands in carbolic.

But in Swardeston that December 1865 there were the best available conditions for a home birth. The hair mattress was covered with an oiled silk cloth and sheets folded into four. The midwife had ready scissors, thread, a calico binder. She guided the head of the baby, heard her first cry, made two ligatures in the umbilical cord, one near the navel the other near the placenta. She twisted out the placenta, wiped the baby’s eyes, washed her gently in warm water, dried her in front of the fire, smeared her with oil, rolled her in flannel, then dressed her in soft warm clothes, fastened with strings. She removed the soiled sheets from Louisa’s bed, washed her, changed her nightdress and cap and made sure everything in the room was in its proper place.

Mother and child survived without mishap. But for the Vicar downstairs, though the birth of a healthy daughter was cause for thanksgiving, it would have been more convenient had God deemed that this firstborn be a boy. He had a stipend of £300 a year and had spent all his own money on the new house. Sons were breadwinners. It was they who continued the family name, sat at the head of table, wrote the sermons, were lawmakers, soldiers, politicians, doctors. The monarch was a woman who was to reign for sixty three years until 1901, but that was an oddity of primogeniture. Queen Victoria had nothing much to do with gender. She was there through divine right, the head of the British Empire. Her crown, orb, sceptre and throne were imperatives of rule. Women were wives, mothers, helpmates, servants. A daughter must needs finds a husband or be a governess or a nurse. ‘Thy desire shall be to thy husband and he shall rule over thee’ the Bible said. Women had no vote, no public voice, their place was in the home.

This vicar’s daughter, born into Christian piety, English country life and entrenched social values, would make her contribution to new ideas of professionalism in nursing. But for a girl, attempts at professional parity with men were countered by censorious reminders of a woman’s place. Most women conformed to the restraints expected of them. A few hit out. In the same year as Edith Cavell’s birth a young Londoner, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson qualified as the country’s first woman doctor. When she tried to pursue her training at the Middlesex Hospital the male students issued a complaint to the management: ‘The presence of a young female in the operating theatre is an outrage to our natural instincts and is calculated to destroy the respect and admiration with which the opposite sex is regarded.’

None the less she found a loophole in the discriminatory rules against women and took and passed the Society of Apothecaries examinations. The Society immediately changed the rules to prevent other women getting the same idea. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson’s response was to set up her own clinic for women. And with her suffragist friends Emily Davies, Dorothea Beale and Frances Mary Buss, she formed the Kensington Society and petitioned for women’s right to vote, go to university, be doctors, be lawyers…

Such feminist campaigning, though, was urban. Swardeston was shielded from change. Accident of birth defined lifestyle. The aristocracy was the ruling class. Socially the vicar was on a par with the squire, but economically he was not much better off than the blacksmith. His status came from his connection to God. Ordained as God’s servant and spokesman, he was the pivotal figure of village life and its moral authority. The 60-foot high tower of the church of St Mary the Virgin loomed over the Reverend Cavell’s parish. Its five bells pealed out the command of devotion. Images of the twelve apostles were cut into the stained glass windows. In this church rites of passage for the villagers were conducted by God’s servant: baptism, marriage, burial.

Edith Cavell was born into the Christian ethic and her father’s insistence on it. From the cradle she was imbued with the duty to share what she had, to help those in pain, alleviate suffering. Life would take her far from Swardeston, its tranquillity and simple ways. Chance would take her into evil times. Through these she would stay true to her roots, her father’s orthodoxy and her mother’s kindness. And from the day of her birth as the vicar’s daughter the Christian command of love was her moral standard.

Praise for Edith Cavell

Souhami’s research is impressive, and seen throughout this powerfully gripping, elegantly written and astonishingly detailed book.

Sue Gaisford · Independent

Cavell is brought sympathetically to life in Diana Souhami’s wonderfully readable biography. Cavell regarded the relief of suffering as a vocation and set up the first Belgian training school for nurses. Although the book’s major emotional thrust deals with Cavell’s imprisonment and death, it is equally fascinating on hospital conditions and the establishment of nursing as a respectable profession for women.

Tina Jackson · Metro

Diana Souhami succeeds triumphantly in bringing the story of Edith Cavell to life, vividly evoking a culture of public duty and Christian self-sacrifice which we have altogether lost.

Jane Ridley · Literary Review

This is a first-class, thoroughly readable biography, providing in-depth detail and brilliant social history – whether it be of life in a 19th-century Norfolk rectory or work in London’s East End or Brussels at the gruesome dawn of war. I don’t know that I’ve ever read a biography that so gripped and moved me.

David Edelsten · The Field