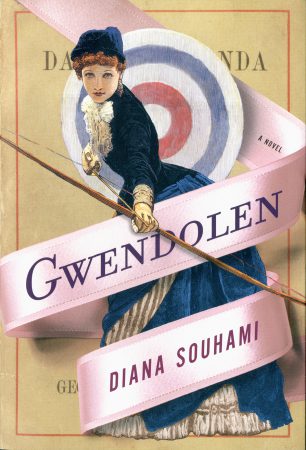

Quercus · 304 pp · 2014

I was winning when I met your gaze. Its persistence made me raise my head then doubt myself. It broke my luck.

Years after she was caught in Daniel Deronda’s eyes at the roulette tables of the Kursaal in Homburg, Gwendolen Harleth writes her confessional to the man whose gaze stays with her. The egotism, naiveté and sensitivity of her youth is evoked with bittersweet wisdom; a passionate remembrance of the events leading up to the marriage she made that broke her spirit, the loss of the man who broke her heart, and her courage to rebuild her shattered life. Moving, original and elegant, this is a bravura re-imagining of the life of one of English literature’s most compelling and contradictory heroines.

Gwendolen Harleth in George Eliot’s novel, is trapped in Victorian culture, economically dependent, educationally deprived, expected to marry to resolve all her problems. I try to liberate her and give her a better time than she gets in the original novel.

D.S.

UK: Hive · Foyles · Waterstones · Amazon · Kindle

US: Indiebound · BAM · Powells · Amazon · Kindle

Read an excerpt

Grandcourt

I was winning when I met your gaze. Its persistence made me raise my head then doubt myself. It broke my luck.

That was our first encounter. A Saturday in September, toward four in the afternoon, the day still light but cool and fresh, Homburg so pretty, so dull, swallows in the eaves of the houses, grape vines on the walls. Little to do but stroll the main street and glance in shop windows at gifts for the rich to give to the rich: ribbons, perfumes, baubles. Only the long, red, stuccoed building in the middle of the street enticed: the Kursaal, the town’s social hub. Madame von Langen, my second cousin, accompanied me there. Through the great door another far door opened to a garden, beyond the garden was a park, beyond the park the Taurus mountains wooded with fir, birch, beech and oak. It was a vista that promised escape from the tight little town and my own despair; a vista that suggested good fortune. A vista that deceived.

In the gilded rococo gaming room naked nymphs cavorted on the ceilings, the players – old, powdered and engrossed, multiplied in the walled mirrors. There was a reverential silence, a sanctity: red or black, the spin of the wheel, the nasal whine of the croupier ‘Faites vos jeux mesdames et messieurs’. I see now my hand gloved in pale grey stretching out to rake gold napoleons towards me. I was exhilarated, elated. I was twenty and born to be lucky. My chosen numbers were mama’s birthday, the day I was born, my father’s age when he died – thirty six, the date mama then married hateful Mr Davilow. That September day at the Kursaal I thought my life might transmute into luck. I began with pittance money but the more I won the bolder I became. I felt destined to win a million before the end of play. I was blessed, the most important woman in the room. Then your gaze deflected me. Your judgmental eyes.

Your gaze mixed attraction with disdain. Your eyes drew me in but implied I was doing wrong. I was beautiful but flawed you seemed to say. I felt the blood drain from my face. It was the coup de foudre, the start of my unequivocal love for you and your equivocal love for me.

Perhaps all that followed I in a moment saw. As if I knew I was to be excluded from where I so desired to belong. I was capricious, reckless and in need of guidance, my life waiting to be defined.

I began to lose heavily. My mood plunged, then rose in defiance. I put ten louis on my chosen number, my stake was swept away, I doubled it, again then again. It took so little time for the croupier to rake from me the last heap of gold. My eyes burned with exasperation. Madame von Langen touched my elbow and whispered we should leave. In my purse only four napoleons remained. As I left, I turned to meet your eyes which I knew were still on me. My look was defiant, yours ironic. Did you respect my daring, my courage to lose?

Mine is a gambling temperament, impulsive, reckless, hopeful. I so wanted the high stakes, the winning chips. To win was to defy the familiarity and fear of loss. Or to court it. It took a punishing journey for me to reach a point of balance between elation and despair.

I had fled to the von Langens from horror at home. I stayed with them in their hired apartment. They took scant notice of me. The Baron, tall with a white clipped moustache, liked to sit in the gardens of the Kursaal and read the Court Columns of The Times. Madame von Langen liked a flutter at the tables, though no more than a ten-franc piece on rouge ou noir.

That evening after dinner we returned to the Kursaal for the music. I wore a sea green dress, a silver necklace, a green hat with a cascading pale- green feather fastened with a silver pin. I anticipated seeing you again. The rooms shimmered with heat from the flares of gas lights, a trio of strings played Mozart and Weber, thick-necked men with cigars talked in groups, women with fans reclined on ottomans. I felt that all who were there admired me – my retroussé nose, almond eyes, pale skin, light brown hair. I heard Vandernoodt say a man might risk hanging for Gwendolen Harleth. ‘There was never a prettier mouth a more graceful walk’ his companion said. I was used to hearing such things.

I flirted and charmed but what I wanted, hoped for, was again to see you. Then you appeared. You stood in the doorway, that detachment you have, your way of observing, your tall, still, figure, dark hair, dark eyes. In a nonchalant voice I asked Vandernoodt who you were. ‘Who’s that man with the dreadful expression?’ He answered he thought you looked very fine, your name was Daniel Deronda and the previous evening he had sat with you and your party for an hour on the terrace but you spoke to no one and seemed bored. He said you were English and a relative of Sir Hugo Mallinger with whom you were travelling. You were staying at the Czarina, the grand hotel in the Oberstrasse.

Daniel Deronda. I still love your name. Here in violet ink is my admission of love and pain, hope and struggle. You will never read it though all is written with you in mind. I know now that I kept a place in your heart and that in a way you loved me, though not as I hoped to be loved, or as I loved you. I hoped I was the woman from whom you might have felt unable ever to be apart, the girl, the woman whom you might have chosen, not to take with you to the other side of the world, but to love and be with until parted by death.

Praise for Gwendolen

In Gwendolen, Diana Souhami performs a bold feat of imagination: what would happen if George Eliot’s final novel were retold from the perspective of its beautiful, complicated, circumscribed heroine? The result is intriguing and moving: a fictional recovery of the woman’s interior experience that lies untold behind the man’s journey to fulfilment, and a powerful meditation upon the nature of creativity. Both an arresting interpretation of George Eliot’s work and a compelling fiction in its own right, Gwendolen will be whispering in my ear next time I go back to Daniel Deronda, reminding me to look for the story behind the story. It is a completely beguiling novel.

Rebecca Mead · Author of The Road to Middlemarch.

Souhami takes to the [novel] as nimbly as galloping Gwendolen might to a fast hunter over bumpy ground… Eliot neglected to find a proper home for Gwendolen. Souhami, with sympathy, mischief and imagination, gives her one.

Independent

In her first novel, highly regarded biographer Diana Souhami… gives Eliot’s beautiful, headstrong anti-heroine her own first-person narrative. This is an act of breathtaking chutzpah… to assume creative responsibility for [Gwendolen] is not for the faint-hearted… It is intriguing, and it is brave.

Guardian

Souhami invents a complex narcissistic interior life for Gwendolen, and she does it with a rhythm of observation and language that stand proudly beside the original. It’s possible to love Gwendolen without having read Daniel Deronda – but Souhami cheekily invites comparison by bringing Gwendolen and a fictionalized George Eliot together at the same dinner party.

New York Times Book Review